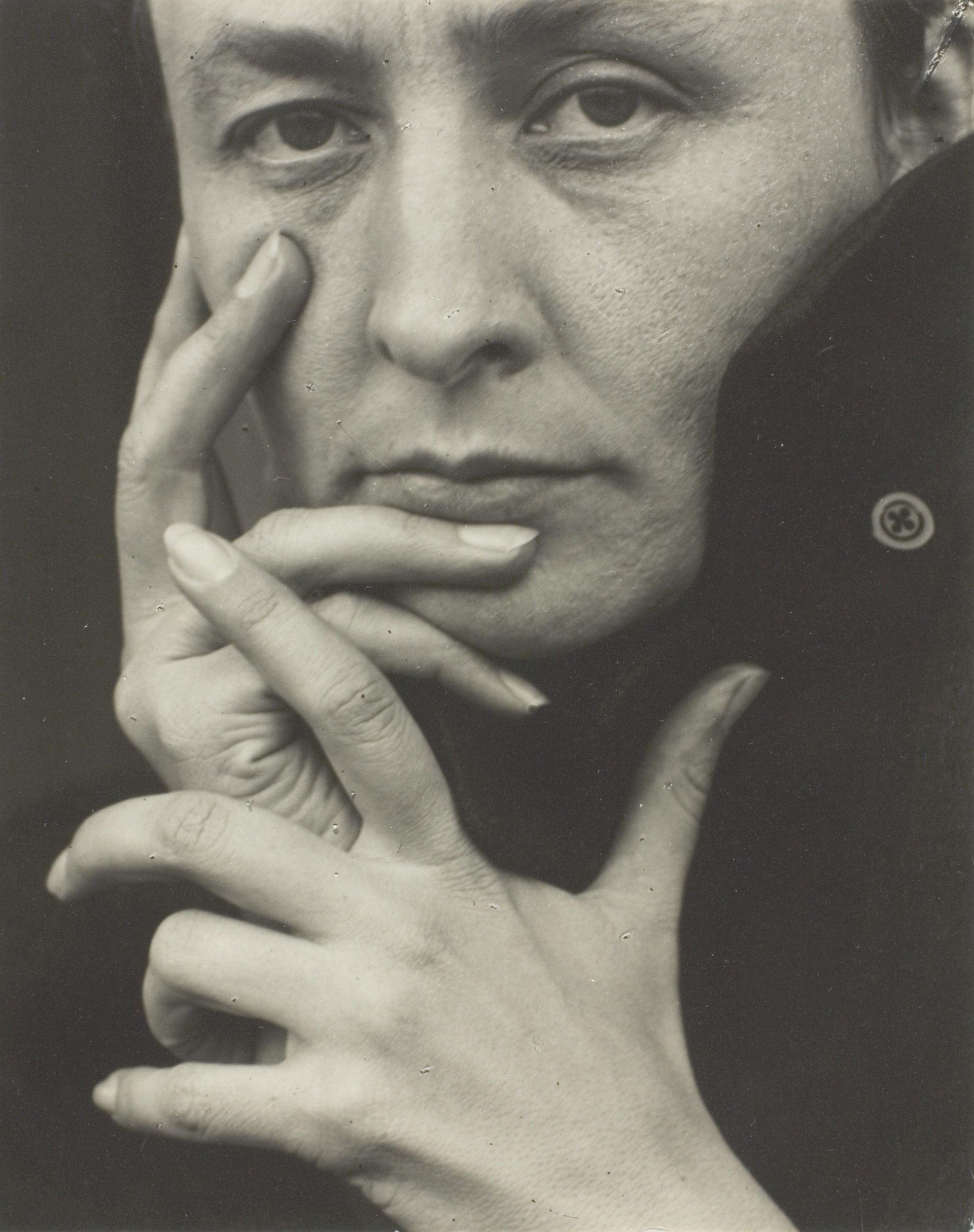

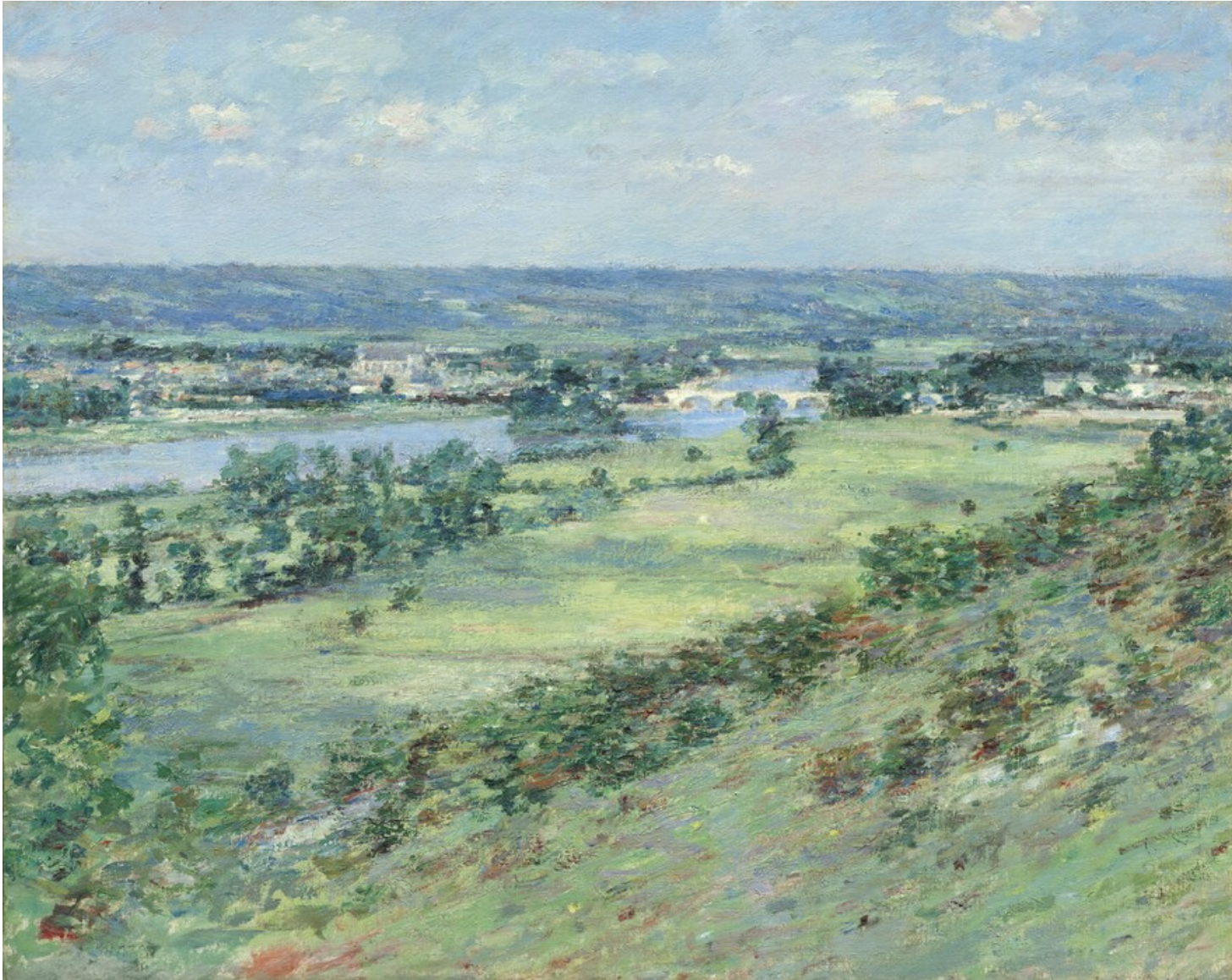

If art lives in the studio, it survives in the photograph. In an era defined by screens and applications, the documentation of one’s artwork is no longer a secondary consideration—it is central to how work circulates, competes, and communicates. The quality of your images may determine whether your work is shortlisted, published, acquired, or passed over. And while this dependency on photographic mediation raises philosophical questions about presence and reproduction, it also demands pragmatic action from artists working today.

The photograph of an artwork is, by nature, a translation—one that flattens, distorts, and re-contextualizes. A painting, when photographed poorly, can lose its texture, its subtlety, even its scale. A sculpture, under the wrong light, becomes an object stripped of dimension and aura. What is required, then, is not the illusion of neutrality, but a form of visual literacy: an understanding that photographing work is an act of interpretation, and must be handled with the same care as any formal decision.

While professional documentation can be costly, it is not inaccessible. A few essential tools—a DSLR or high-resolution smartphone, a tripod, and consistent natural lighting—can yield powerful results. The choice of backdrop, camera angle, and post-production editing should enhance, not obscure, the integrity of the work. Color correction must be done with restraint; cropping should be meticulous. Above all, the goal is fidelity—an image that reflects, as closely as possible, the lived experience of the piece.

In the digital art economy, where juries and curators often encounter your work first (and sometimes only) through a screen, documentation is no longer just a technical requirement. It is an act of authorship. Each image should assert the value and seriousness of the practice it represents. Mediocre documentation doesn’t just misrepresent the work—it diminishes its opportunity to be seen.