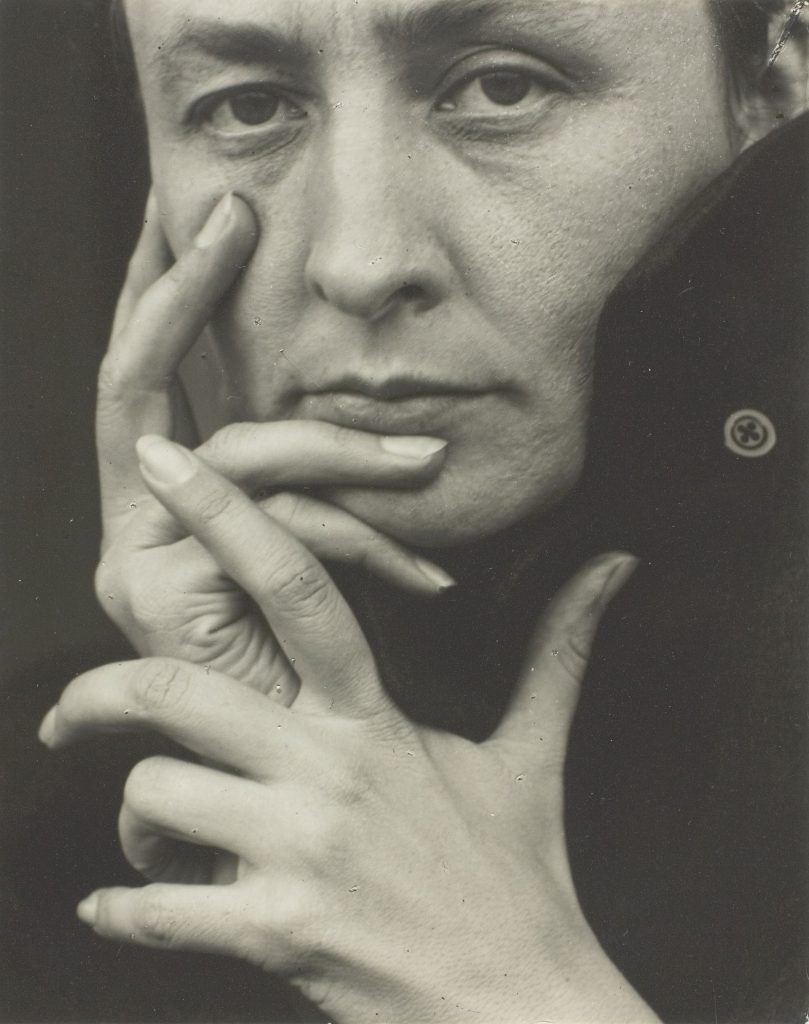

Born in 1887 in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, Georgia O’Keeffe emerged as a pioneering force in American modernism through a combination of fierce independence and radical simplicity. After early training at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League in New York, O’Keeffe became disillusioned with traditional academic instruction and ceased painting for several years. Her artistic voice reawakened when she encountered the philosophies of Arthur Wesley Dow, whose emphasis on personal expression and design over realism had a profound influence on her developing aesthetic. It was through a series of abstract charcoal drawings sent to a friend that O’Keeffe caught the attention of Alfred Stieglitz—photographer, gallerist, and the man who would become her husband and advocate.

O’Keeffe’s early work focused on pure abstraction, rare for an American artist at the time, and quickly evolved into the iconic visual language that would define her long career: enlarged flowers, bleached animal bones, and vast desert landscapes. In the 1920s and 1930s, her large-scale flower paintings—often mistaken for anatomical references—challenged viewers with their bold scale and subtle gradations of color. By the 1940s, O’Keeffe had increasingly turned toward the landscape of the American Southwest, particularly New Mexico, where the clarity of light and openness of space offered her both subject and sanctuary. Her later work remained stylistically consistent while exploring deeper themes of solitude, scale, and permanence.

At the core of O’Keeffe’s work is a radical simplification of form and a deep attentiveness to the natural world. Her paintings are meditations on perception—stripping objects of context and presenting them in ways that are both intimate and monumental. Works like Jimson Weed, Black Iris, and Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue reveal her fascination with line, color, and structure, but also carry metaphysical undertones. She resisted the symbolic interpretations often imposed by critics, insisting that her work was about the experience of looking closely and deeply. In doing so, O’Keeffe opened a new visual territory where emotion was not loud, but deliberate.

Georgia O’Keeffe holds a singular place in 20th-century art. Often referred to as the “Mother of American Modernism,” her influence reaches far beyond her iconic imagery. She carved out a space for women in a male-dominated art world without conforming to its expectations. Her commitment to place, process, and autonomy continues to resonate with artists across disciplines. Through her work, O’Keeffe demonstrated that stillness, when seen with clarity and intention, can be as powerful as provocation.